Se sconfortati dalle prospettive poco incoraggianti dell'economia - e forse anche dei mercati - nel breve-medio periodo siete desiderosi di affrontare la questione con una prospettiva di lungo periodo troverete interessanti i link che vi propongo qui sotto:

- qui potete ascoltare una recente intervista di Robert Shiller che spiega come utilizzando il rapporto P/E10 (nel quale gli utili - earnings - sono mediati su 10 anni in termini reali) sia possibile avere una previsione decentemente accurata dei rendimenti azionari futuri su una scala di tempo di 10-20 anni. La buona notizia è che siamo lontani dai picchi della fine degli anni novanta, in cui la valutazione del mercato era persino superiore di quella che precedette la crisi del '29, la cattiva è che siamo ancora considerevolmente al di sopra della media storica (circa 22 vs. 15). La conclusione: probabilmente è lecito aspettarsi un rendimento annualizzato di circa il 2-3% in termini reali. Sulla questione poi della valutazione del mercato azionario rispetto a quello obbligazionario sentite cosa dice Shiller: The second point that Siegel made is in relation to the interest rate environment. His comment was that, based on his research, that periods that have high interest rates, the [market] P/E multiple, historically, has been much lower, and in periods of low interest rates, such as we have today, that multiples, the normal multiples, that is, would be significantly higher, and that we should be adjusting for that in terms of what a fair value is. What’s Shiller’s view on that? RS: This is a complicated point. One thing is whether we look at nominal or real interest rates. He assumes that Jeremy Siegel is looking at real, like the TIPS in the US or the inflation index. But we don’t have a history of that before 1997.

Look at nominal rates. If you look at nominal long-term rates and you compare them with the P/E ratio back to 1881, there were periods where it looked Jeremy was right, but it hasn’t been consistently right. I think that’s a half truth.

The other thought is, okay, long term interest rates are very low now, so that would seem to say, the stock market is very high, and also commodities and everything else should be high. There’s some truth to that, but the other question is, how reliably are those long term rates going to stay low?

The real question that people really want to know the answer to is how do we forecast the market?

I don’t think that anyone has found that long term rates offer a significant way of forecasting the market.

DR: Last question. You mentioned that the long-term average multiple is 15 times 10-year earnings, currently its about 22 times, which you said, is a bit on the high side, not egregiously… Based on that, what kind of returns could investors expect over a 10 year period, coming from an environment like the one we’re in today?

RS: Based on our forecasting regressions, its a tough call, whether stocks or bonds will pay more over that period. Its not an inspired time.

The Campbell-Shiller forecasting regression suggests positive returns, but not teriffic.

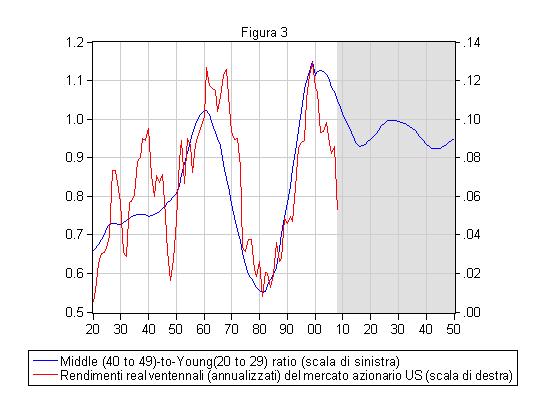

- qui invece potete leggere un interessante post di Bill Gross sulla relazione tra la crescita demografica e quella economica. La tesi è molto chiara: la diminuzione del debito (sia privato che pubblico) nei prossimi anni si combinerà con una decisa diminuzione del tasso di crescita della popolazione aumentando il rischio di deflazione e diminuendo il tasso di crescita dell'economia:

The danger today, as opposed to prior deleveraging cycles, is that the deleveraging is being attempted into the headwinds of a structural demographic downwave as opposed to a decade of substantial population growth. Japan is the modern-day example of what deleveraging in the face of a slowing and now negatively growing population can do. Prior deleveraging periods such as what the U.S. and European economies experienced in the 1930s exhibited a similar demographic with the lowest levels of fertility in the 20th century and extremely low population growth. Things did not go well then. Today’s developed economies almost assuredly offer substantially less population growth than the 1.5% rate experienced over the prior 50 years. Even when viewed from a total global economy perspective, population growth over the next 10–20 years will barely exceed 1%.

The preceding analysis does not even begin to discuss the aging of this slower-growing population base itself. Japan, Germany, Italy and of course the United States, with its boomers moving toward their 60s, are getting older year after year. Even China with their previous one baby policy faces a similar demographic. And while older people spend a larger percentage of their income – that is, they save less and eventually dissave – the fact is that they spend far fewer dollars per capita than their younger counterparts. No new homes, fewer vacations, less emphasis on conspicuous consumption and no new cars every few years. Healthcare is their primary concern. These aging trends present a one-two negative punch to our New Normal thesis over the next 5–10 years: fewer new consumers in terms of total population, and a growing number of older ones who don’t spend as much money. The combined effect will slow economic growth more than otherwise.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento